Discover more from Flashlight & A Biscuit

Welcome to Flashlight & A Biscuit, my Saturday-morning Southern culture offshoot of my work at Yahoo Sports. If you’re new around here, why not subscribe? It’s free and all.

First, a hearty welcome to those who’ve just joined us. Between Buc-ees, the Diablo Sandwich and those one-star Waffle House reviews, we’ve seen a huge jump in subscriptions. Here’s where the name of this newsletter came from, and here’s our back catalog if you’re looking for some holiday reading material. Today, we’re focusing on the spirit of this weekend.

Sam Laughon was the bright-eyed, lanky son of a Methodist preacher, born in Lancaster County, Virginia on the shores of the Rappahanock River. His father, the Rev. Theodore Laughon, preached all over the state, and his mother Adelaide provided a loving home for Sam and his little sisters, Dorothy and Ella. Life was idyllic and pure, vintage Americana.

Right around the time Sam turned 16, the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Company in Quincy, Massachusetts, about 600 miles up the coast from Sam, started work on a heavily-armed, light-armored New Orleans-class cruiser. Her name: U.S.S. Quincy.

In the summer after Sam graduated from high school, work wrapped up on the Quincy. Completed at a cost of $8.2 million, she launched that June, sponsored by Catherine Frances Loevering Adams Morgan, of Morgan Stanley and J.P. Morgan fame. (Ah, the tangled lineage of the Boston elite.)

Sam believed deeply in the value of education, and plotted a career path that would take him through college and beyond. As Sam began studies at Richmond College — now the University of Richmond — Quincy toured the world, evacuating refugees in the Mediterranean during the Spanish Civil War and traversing the Pacific between California and Hawaii.

While the Laughon family lived in Lynchburg, Virginia, Sam fell hard for a young woman named Gladys, who just happened to be the best friend of his sister Dorothy. He proposed, she accepted, and they began making plans for a life together. One hemisphere south, Quincy embarked on a goodwill tour of South America.

Sam decided to pursue graduate studies at Johns Hopkins University right around the time hostilities were flaring up in Europe. At the same time, Quincy patrolled the North Atlantic in a pose of watchful neutrality, often traveling in the company of the U.S.S. Yorktown, the aircraft carrier now decommissioned and docked outside Charleston, S.C.

Then Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, and all priorities changed.

As much as Sam believed in the value of education, he believed in his country more. He’d enlisted in the Navy in September 1941, and he dropped out of Johns Hopkins to report for active duty in January 1942. On Feb. 13, 1942, he was appointed a midshipman in the Naval Reserve. The Quincy, meanwhile, wrapped up a patrol of the waters around Denmark and returned to New York for upgrades and reconditioning.

Sometime early in 1942, Sam posed with his parents in his dress whites, and the smiles on the faces of Theodore and Adelaide — people who knew deprivation, people who had fought their way through the Depression while trying to raise a family — are the smiles of people who know their son is following his true calling.

Next to them, Sam is beaming, a wide, open smile of a young man ready to take on the world, and convinced he’ll win. It’s here, just after that photograph was taken, that the fates of man and ship intertwine.

On May 29, 1942, Ensign no. O-120209, Samuel Walter Laughon, reported to the Navy Yard in New York and first set foot aboard the Quincy. At this point, we have to go from the particular to the general, because Sam’s letters home have been lost to time.

On June 5, 1942, the Quincy, with Sam aboard, set out for the South Pacific, traveling through the Panama Canal and stopping in San Diego. By the first week of August, she reached the Solomon Islands, and her crew saw immediate action. On Aug. 7, 1942, her guns shelled several crucial Japanese installations on the critical strategic ground of Guadalcanal Island.

Then came the Battle of Savo Island.

In the predawn hours of Aug. 9, 1942, the captain and most of the crew of the Quincy were asleep, catching up on rest after several tense days of battle. As they slept, Japanese cruisers wound their way through multiple patrols, sliding through when they were at their widest margins apart from one another.

Watchmen on the Quincy observed flares being dropped over other ships to illuminate them for Japanese gunners. Just as Quincy’s horns sounded general quarters — battle stations — Japanese searchlights lit up the cruiser, and shells began falling. Quincy’s guns weren’t yet ready, and the ship was caught in a crossfire between the Japanese ships Aoba, Furutaka, and Tenryū.

“We could see [the shells] coming,” one petty officer later said. “They were just like red lanterns coming straight at us.”

The Quincy returned fire for as long as she could. The men on deck ducked to avoid the carnage. An officer stepped out of the pilot house and bellowed, “Let’s be men, not mice!” Those were his final words; a shell hit him moments later.

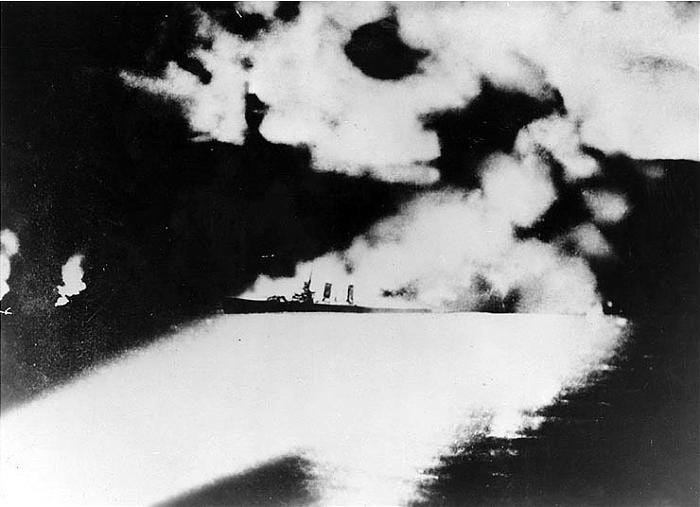

Ambushed and pinned down, the Quincy didn’t have a chance. In one of the most haunting photographs of the war, Quincy, mortally wounded, sinks toward the waterline, trapped in the blinding Japanese searchlights:

Quincy took hits from an estimated 54 shells and three torpedoes. The Japanese cruisers circled around her as she burned, the lights from the flames so bright that the Japanese could turn off their beams.

The ship began listing to port, sinking at its bow. Shortly after 2:30 in the morning, she capsized and sank, plowing bow-first into the ocean floor. An artist captured a version of the scene in a famous image later printed in Life magazine:

The Battle of Savo Island was the United States’ worst naval defeat in a fair fight, a demoralizing blow to the Pacific fleet’s heart. Three ships were lost, with more than a thousand dead, in just 37 minutes. So many ships would eventually sink in the waters around the Solomon Islands that the area would gain the ghoulish nickname “Ironbottom Sound.” The Quincy alone lost 370 men.

Sam Laughon was one of those.

He was apparently on the bridge when the shelling began. That seems a better fate than being one of the men trapped below decks, clambering in darkness to get to fresh air. The Japanese targeted Quincy’s bridge early in the shelling, and the destruction was immediate and devastating.

It’s impossible to know Sam’s fate. Perhaps he survived that initial bombardment. Perhaps he was the one who called on his men to stand up and fight. Perhaps he was one of those who, in Quincy’s final moments, ordered the firing of a shell that demolished the bridge of another Japanese cruiser. I wish I knew. I want to believe he died a hero’s death, but the truth is, by making that commitment to defend his country, he already was one.

He had walked into the war with open eyes and a resolute heart. It stands to reason he would have faced his end the same way.

Sam was declared deceased one year and a day after the battle, on August 10, 1943, and awarded a posthumous Purple Heart. The Quincy would lie undiscovered at the bottom of the sea for 50 years. She still sits 2,000 feet below the surface today, broken, battered, but upright on the sea floor.

Nineteen months after the Battle of Savo Island, Sam’s sister Dorothy gave birth to a daughter. That daughter would grow up to meet a nice college boy, and a few years later, those two foisted me on the world. Sam’s name is engraved on a white marble plaque at my old college, and I probably walked right past it a hundred times before I realized my connection to it.

Eighty years ago, someone less than half my age laid down his life for his country. I’m proud as hell that his blood runs through my veins, even if it took me way too long to really understand what that meant.

I don’t come from a family with an extensive tradition of military service; Sam was the exception rather than the rule. Perhaps for that reason, Memorial Day hasn’t resonated with me the way it really should — not as just an extra day to hang out on the water or in the mountains, but as a time to quietly reflect on honor and sacrifice, too. (Emphasis on “quiet.” I’ve had enough of theatrical, performative displays of patriotism.)

Sam’s death scarred the Laughon family. His parents were never the same after 1942, and his sister Dorothy never opened up about him. Although there are at least two family members named for him, almost everyone who ever knew Sam Laughon is now gone. As best I can tell, there’s no recording of the sound of his voice, nothing remaining of him other than a handful of photographs Dorothy’s daughters share on family email chains every few years. My daughter did a school report on him — she uncovered much of the information on the Quincy above — and we’ve tracked him through public records and government databases. But those are the facts of a life, not the story of it. Sam and the other men and women who sacrificed their lives for America deserve a better legacy.

There’s a memorial bearing his name in the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines. I don’t know if anyone in our family has ever visited it, but I’d like to see it someday, just to say thank you, and to keep his story alive for future generations.

I appreciate you reading this, and I hope your Memorial Day is safe and reflective. If you have a military family member’s memory of your own you’d like to share below, I’d be honored to read it.

Catch you next week, friends.

—Jay

[Many thanks to the dedicated Laughon descendants — Mary, Kathy, Crystal and Riley — for their invaluable research and documentation of Sam’s story.]

This is issue #57 of Flashlight & A Biscuit. Check out all the past issues right here. Feel free to email me with your thoughts, tips and advice. If you’re new around here, check out some of our recent hits:

What is a Diablo Sandwich, anyway? Solving a “Smokey and the Bandit”mystery

A journey to the heart of the real America: Buc-ees.

What it was like to cover the Beijing Olympics inside a locked-down China

Beneath the waters of the South’s most haunted lake

How Richard Petty learned that Daddy won’t always let you win

The joy of a really terrible Southern accent

If you dig this newsletter, share it with your friends. Invite others to the party, everyone’s welcome.

Subscribe to Flashlight & A Biscuit

Kick back with some tales of Southern culture, sports, food and music from Jay Busbee. Grill's already hot; drinks are on ice. Pull up a chair.

Thanks for sharing this story, Jay. These stories are what Memorial Day is all about.

My condolences. Thanks for writing about Sam's Service. Wonderfully written. God Bless You and Yours Jay.