Discover more from Flashlight & A Biscuit

Lake Lanier: Secrets of the South's most haunted lake

Don't think too much about what might lie beneath still waters.

Welcome to Flashlight & A Biscuit, my Southern sports/culture/food offshoot of my work at Yahoo Sports. Thanks for reading, and if you’re new around here, why not subscribe? It’s free and all. Today: put on the sunscreen and crack a cold one before the creepiness begins …

On any given afternoon when the North Georgia temperature rises above 50 degrees — which is to say, any afternoon other than a six-week span around New Year’s Day — Lake Lanier is a vast swirling ballet. Speedboats drag skiers and tubers across the steep wakes left by wailing cigarette boats. Jet skiers crisscross in DNA-style patterns, confident in the belief that since God protects fools, drunks and little children, they’re covered from multiple angles. Along the banks of the islands that dot the lake, rope swings dangle tantalizingly from high branches. Boaters and their passengers everywhere prop their feet up on their life jackets and bliss out to the bro-country of Luke Bryan and Jason Aldean.

And every single one of them, whether they know it or not, is cruising right over the bones of dead towns.

Last week, Gen Z discovered — via a viral TikTok clip — that Lake Lanier is haunted as hell. Not to pull the that’s-cute card — every generation has to discover legends for itself, and every generation’s convinced it’s the first to do so — but my TikTok friends, around here we’ve known about the sinister history of Lake Lanier for years. Decades, even. Want to hear the real story?

Shortly after World War II, the Army Corps of Engineers decided to dam up the Chattahoochee River to create a reservoir that would generate power for, and prevent flooding of, the city of Atlanta. After considering a number of locations — including one disturbingly close to where I now live — the Corps began buying up land in and around the tiny town of Oscarville in Forsyth County.

“Buying up land” is one of those bureaucratic phrases that’s doing a whole lot of ugly work. The Corps had to move 250 Oscarville families off their ancestral land, along with six churches and 15 businesses, and paid them something on the order of $40 to $50 ($420 to $530 in today’s dollars) per acre for their property.

Imagine that: the government stepping in, buying you out, moving you off your homeland, and then burying it under billions of gallons of water where people now lounge. I won’t get political here, I’ll just say that simple, 30,000-foot assumptions about why people believe what they believe often aren’t anywhere close to the truth.

Anyway, the buyouts started in 1948, construction on Buford Dam began in 1950, and the lake reached its full level in 1959. Beneath the waters: roads, buildings, bridges, trees … an entire community gone as the river rose. When “finished,” Lake Lanier covered 39,000 acres, with 691 miles of shoreline.

(This flooding-out wasn’t an uncommon practice. It’s one of the story threads running through the Netflix series “Ozark,” much of which is filmed on Lake Lanier despite supposedly being located in Missouri. It’s also the basis for the backstory of “Deliverance.” If you only know the James Dickey novel-turned-Burt Reynolds movie via dueling banjos and squealing pigs, you’re missing out on unsettling brilliance. The tale of smug city types paddling down a river one last time before the strange-talking locals lose their homes to the flood is an American classic that hasn’t lost any of its power or resonance.)

To this day, you can see evidence of the land that was once there. More than 160 tiny islands dot the lake … islands that were once the tops of hills:

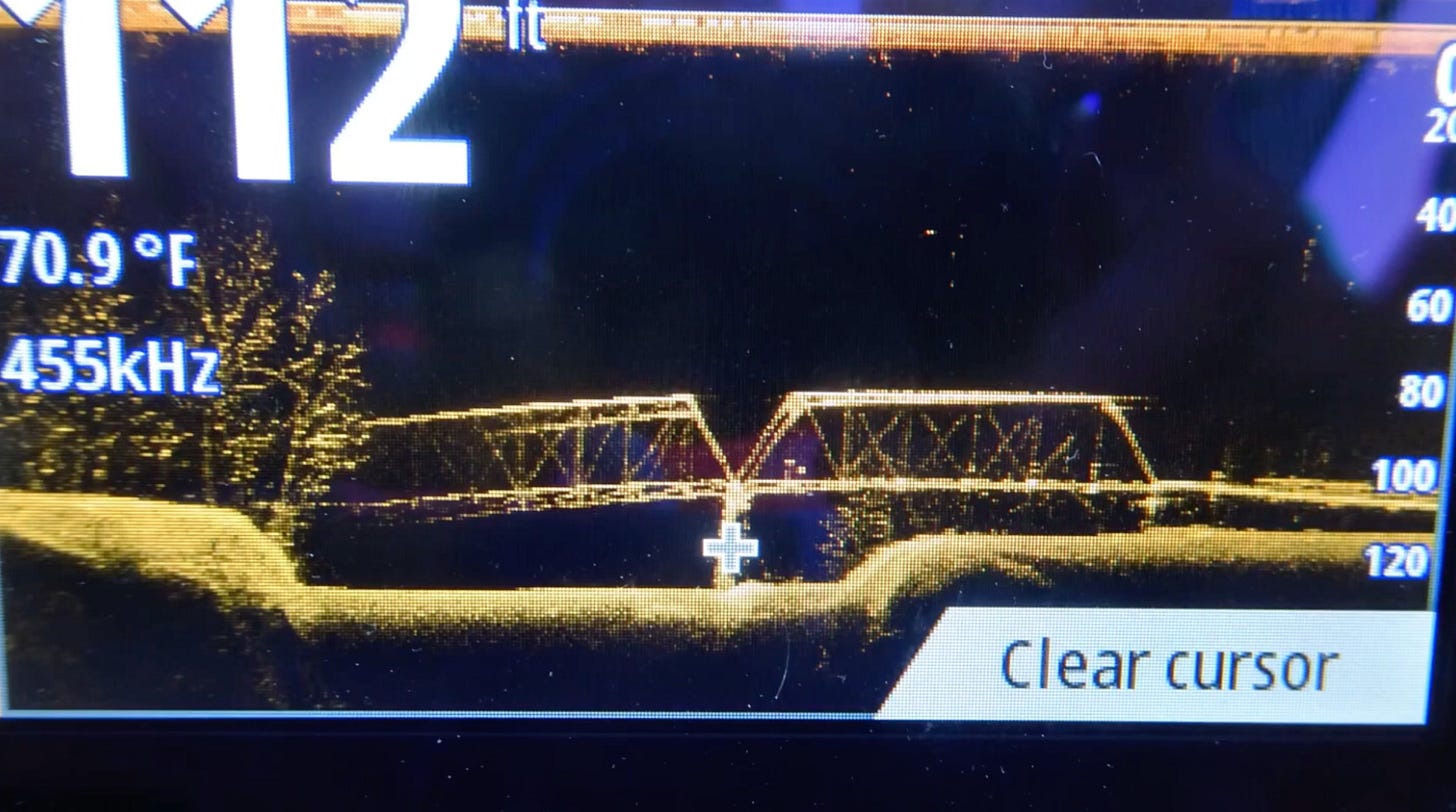

Every so often, you’ll get a more concrete, man-made reminder of what lies beneath the waters. Divers have ventured into the depths and filmed piles of rubble still stacked all these years later; cinder blocks and wood planks are still obvious and visible. Sonar has shown even more detail; here’s the span of the Lights Ferry Bridge more than 100 feet below the surface:

According to local legend, the spans of the bridge were sold for scrap, but the water rose too rapidly, and several spans were left behind.

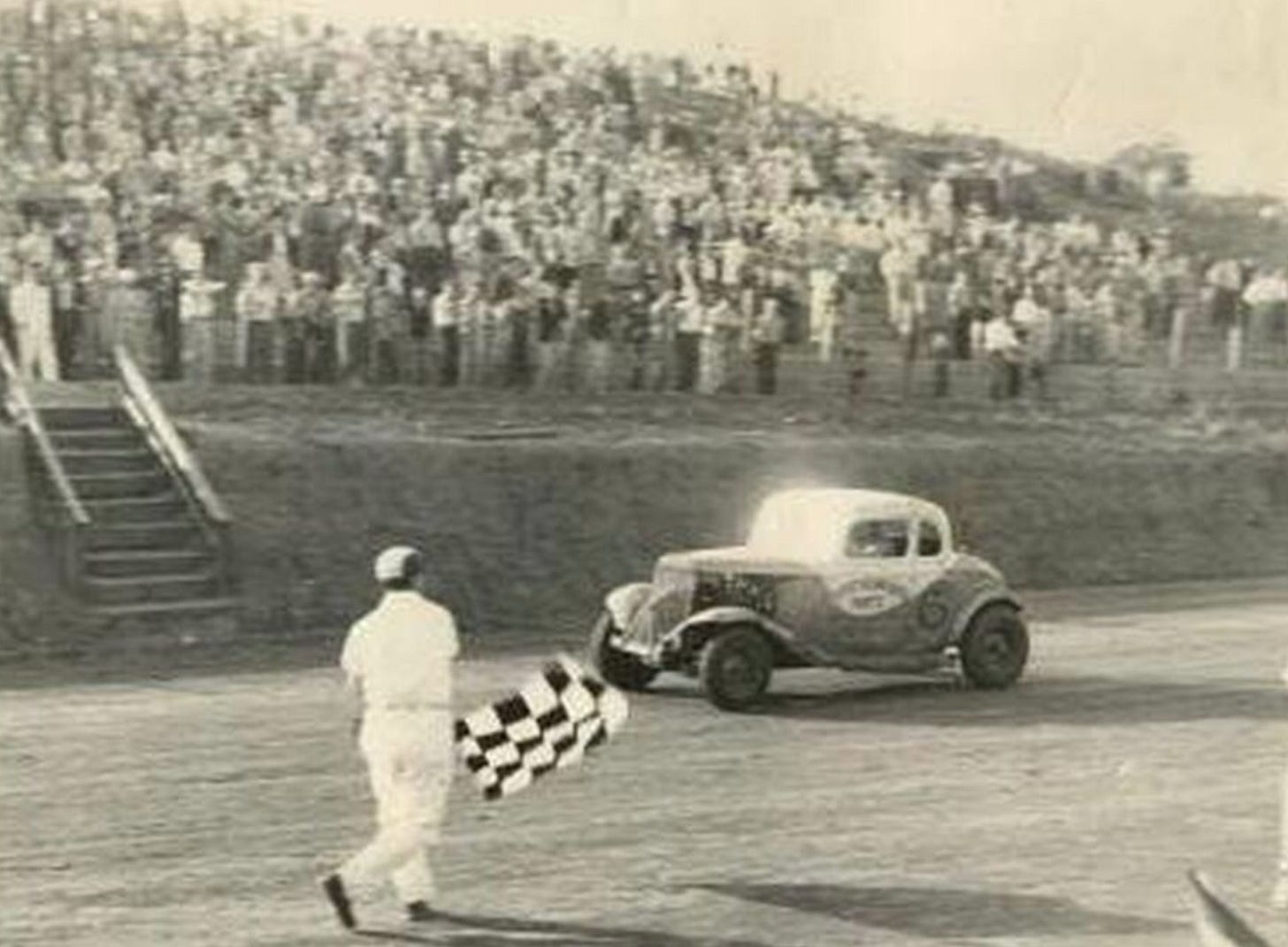

Back in 2007, a drought was ravaging the South, and Lake Lanier’s waters receded so far that docks stretched over only mud and silt. The drought exposed the concrete grandstands of long-buried Gainesville Speedway. Built in 1949 to capitalize on the burgeoning trend of Southern stock car racing (hey, what ever happened with that?) the track hosted a Georgia driver with one of the great names in racing history — Gober Sosebee — and once witnessed an all-too-rare victory by a woman, Sarah Christian of Dahlonega. These once-full stands now lie deep below murky waters, surfacing only in dire conditions:

Yeah, yeah, all this talk of buried towns and race tracks is fascinating, you’re saying, but I was told there would be haunting. Kind of bloodthirsty, aren’t you? Fine. Here’s the gruesome.

Lake Lanier was never designed as a recreational hangout, but its glassy waters and gorgeous views draw Georgians by the millions. That’s wonderful in theory, not so much in practice when you think about what’s beneath those waters.

When the Corps of Engineers flooded the land, crews rode around the water and lopped off the tops of trees that still rose above the waterline. The Corps then brought the lake to full pool, but those high stumps are still down there, not far below the surface, ready to catch and grasp anything that falls, or drifts, too far below the waterline.

And then there are the cemeteries. The families that lived on that land for so many years had buried their ancestors there; an estimated 20 cemeteries were relocated away from the lake’s footprint. But it’s all but certain some family plots still remain.

The lake is cold — 52 degrees — dark and deep, as much as 160 feet in some places. The muck of the floor makes visibility nearly impossible, and experienced divers have called it among the most dangerous spots they’ve ever dived.

Plus, the surface of the water is not exactly placid, not when you’ve got a bunch of hot tub salesmen and tanning-salon owners with more credit lines than sense tooling around at high speeds. As many as a dozen visitors die at the lake each year, and local authorities note that it can be very difficult — bordering on impossible — to recover them.

That was the case with the lake’s most notorious victim, a young woman named Susie Roberts. In April 1958, she lost control of her car and plunged into the lake off Dawsonville Highway. Her car settled in 90 feet of water, caught in a deadfall of those broken trees from long ago.

A year after the accident, divers found the body of another woman believed to have been a passenger in the car … but neither the car itself nor Roberts’ body could be found in those dark, cold, zero-visibility waters. It wasn’t until 1990 when construction crews on a bridge expansion finally found the car.

A slightly less grim story — as long as you’re not in the water — is the tale of the Chicken Truck. According to this particular legend, the catfish in Lake Lanier can grow to the size of wheelbarrows. So when a chicken truck plunged into the lake in the 1980s, onlookers could see catfish popping up out of the water to swallow chickens whole.

I’m headed up to the lake in a few weeks, and you bet your ass I’ll be watching for those damn catfish … and everything else that’s grim in the lake. I’ll also be keeping an eye out for another glimpse of this good ol’ boy I once saw, an engineering genius who transformed a Fiero into a watercraft.

Now that’s the lake life I love.

(Sources: Speedway and Road Race History, 11 Alive, Gwinnett Citizen)

That’ll do it for this week. Recommendations, menus & street art will be back next week; the last few days I’ve been swamped writing about the PGA Championship. Writing about sports … what a novel concept. But hey, if you’ve seen/heard/eaten something all of us here ought to check out, let me know. We’ve got a growing community here at F&AB, so let’s take advantage of it.

Anyway, stay safe and don’t go diving too deep …

-Jay