Fear and ponies: The glorious, gonzo ecstasy of the Kentucky Derby

Revisiting a literary classic and drinking a fine concoction on the first Saturday in May. Riders up!

Welcome to Flashlight & A Biscuit, my Southern culture offshoot of my work at Yahoo Sports. Thanks for reading, and if you’re new around here, why not subscribe? It’s free and all.

Today: It’s Derby Day! Let’s get gonzo! Plus: stick around for a bonus Mint Julep recipe that’ll have you rolling in the bluegrass like a born Kentuckian.

I love the Kentucky Derby. I realize this is about as revolutionary a statement as saying “Air is good for you” or “puppies are cute,” but in an era where everyone on your social media is braying about how EVERYTHING SUCKS1, I offer this humble proposition: it’s OK to enjoy things that are fun. And oh, is the Kentucky Derby fun, whether you’re decked out in your seersuckers and thousand-dollar engineering-marvel hats, writhing in the drunken pit of madness that is the infield, or hanging with friends around a TV and placing bets on horses you’d never heard of three minutes ago.

If you’ve never been to Louisville for the Derby, put it on your bucket list. No, seriously, right now. If you don’t have a bucket list, start one and put GO TO THE KENTUCKY DERBY at the top. It’ll cost you money. You’ll have to wrangle travel arrangements with the deft hand of someone trying to smuggle a hostage out of a hostile foreign nation. You’ll end up more drunk than you expected and much poorer than when you started the day — how could that damn horse lose when it was five lengths ahead in the final turn? — and your feet will burn like you’ve walked over hot railroad spikes.

But it’s all worth it. The sight of the twin spires of Churchill Downs … the sounds of the bugler signaling post time and the thunder of hooves … the scent of mint and bourbon and dirt and sweat and perfume … the taste of a Mint Julep over crushed ice … the experience of plugging into the psychic charge of the 170,000 people around you, knowing that for two minutes, a substantial segment of the nation is focused on the very spot in the universe where you’re standing … it’s all glorious and absurd and joyful and communal in a way that verges on spiritual, at least until you throw up on your shoes.

No one captured this combination of sublime and profane better than Hunter S. Thompson, who — 52 years ago this week — detonated a warhead of a dispatch from within Churchill Downs. His “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved,” written for a now-forgotten magazine that vaporized just months after publication, stands as one of the high-water marks of an entire generation’s approach to storytelling. It’s the earliest appearance of what would come to be known as gonzo journalism — the deadbeat dad of a thousand groundbreaking stylistic innovations and a billion godawful imitations that followed in its greasy wake.

Every young white male journalist born before, oh, 1990 goes through a Hunter S. Thompson phase.2 You stumble across a copy of “Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas,” your mind gets blown open like someone pointed a Roman Candle inside a Coke can, and suddenly you’re ranting about those filthy whoremongers in Congress and that sweaty hog-wattled Richard Nixon, swilling Jack Daniels, wondering how exactly you’d go about scoring some mescaline, and sporting an ill-fitting bucket hat and cigarette holder3.

(Confession: I did pretty much all this. Back in college, I wrote a godawful story with the witty HST-very-lite headline of — I can’t believe I’m admitting this — “Beer and Donuts on the Campaign Trail.” And later, after college, I made a pilgrimage to Thompson’s beloved Woody Creek Tavern in Aspen, where a server’s ticket on the wall bore HST’s scrawled promise not to throw any more smoke bombs during business hours. I drove up to the gates of Owl Farm, Thompson’s home, but it was late, I was unarmed, and I didn’t want to run the very real risk of getting a shotgun blast to the face, so I let him be.)

Born and raised in Louisville, Thompson was one of the earliest architects of what would be called New Journalism — a form of literature that places the author’s experience and perspective at the center of the story, demolishing the idea of objective journalistic truth. (Hate to break it to you, millennials, but Boomers were neurotically self-obsessed decades before you.)

For Thompson, New Journalism meant hurling himself right into the center of a situation, causing chaos, and writing about what resulted — as well as what could have resulted, what should have resulted, and what Thompson believed resulted. Thompson and facts were not always on speaking terms.

Read from half a century’s distance, “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved” is almost quaint, a disorganized ramble of half-followed thoughts, performative posturing, dubious word choices and outright fabrications. It’s also rumbling and propulsive, barreling across the page (well, screen) like a bald-tired convertible Thunderbird weaving from emergency lane to center line and back again. You can love it or you can loathe it, but you can’t ignore it.

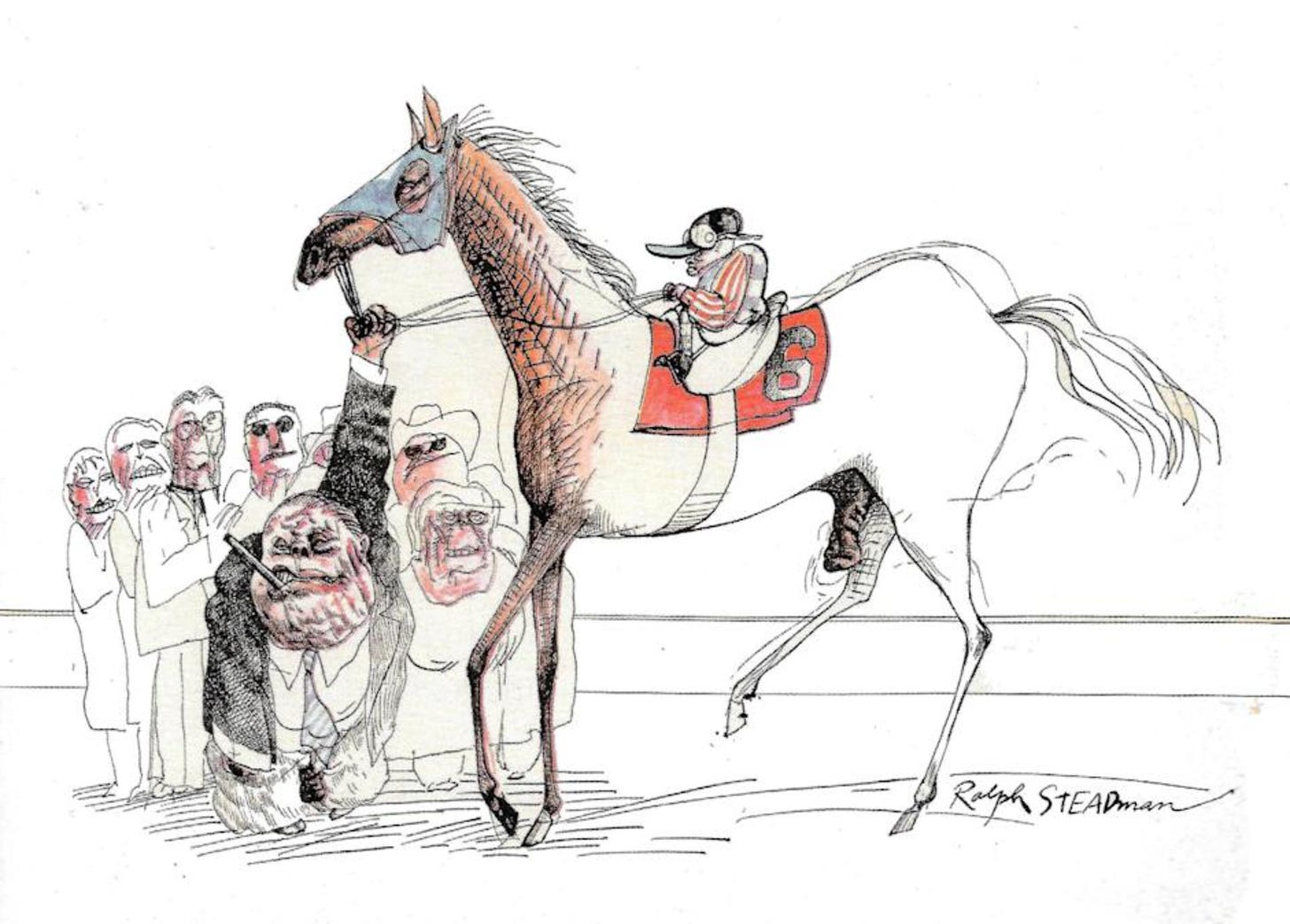

All you need to know about “TKDIDAD” as a piece of sports reporting is this: HST dispenses with the entire race recap in two sentences at the bottom of an unrelated paragraph in the middle of the article, and mentions the name of the race winner only once. The story is about the creation of the story — in this case, Thompson and artistic collaborator Ralph Steadman meeting, trying to score credentials, causing havoc, escaping punishment, ravaging themselves and their surroundings, and finally collapsing into a whiskey-soaked pile of exhaustion. The decadence and depravity swirling around the Derby, Thompson suggests, is highly contagious and damn near lethal.

Here’s his description of how Derby day unfolds: “Thousands of raving, stumbling drunks, getting angrier and angrier as they lose more and more money. By midafternoon they’ll be guzzling mint juleps with both hands and vomiting on each other between races. The whole place will be jammed with bodies, shoulder to shoulder. It’s hard to move around. The aisles will be slick with vomit; people falling down and grabbing at your legs to keep from being stomped. Drunks pissing on themselves in the betting lines. Dropping handfuls of money and fighting to stoop over and pick it up.” Not exactly the reality of the day, but even now, not as far from reality as Churchill Downs elders want to admit.

It’s the literary equivalent of a guitar solo by someone who isn’t quite sure whether to play the guitar or swing it like a baseball bat. No thread is too absurd to pursue to its absurd conclusion: “Steadman is now worried about Fire. Somebody told him about the clubhouse catching on fire two years ago. Could it happen again? Horrible. Trapped in the press box. Holocaust. A hundred thousand people fighting to get out. Drunks screaming in the flames and the mud, crazed horses running wild. Blind in the smoke. Grandstand collapsing into the flames with us on the roof. Poor Ralph is about to crack.”

Steadman’s illustrations drive the entire message home, a slimy stake to the heart of Louisville society. The denizens of the Derby, as captured by Steadman’s pen, are misshapen ghouls, jowly and sweaty and altogether loathsome:

There’s no grand conclusion here, no triumphant reckoning either for Thompson or the old bloodlines of Louisville. The article ends with Thompson booting a sweating, vomit-stained, mace-covered Steadman out of his car at the airport curbside, bellowing “We can do without your kind in Kentucky!” A Louisville native, Thompson and his hometown forever regarded one another with suspicious eyes, and you can feel both the disgust and the envy radiating out of Thompson’s words throughout the story.

Was it truth? Fiction? Both? Who cares? It was a rabid ferret thrown into the cocktail party of American journalism. Bill Cardoso, an editor and running mate of Thompson’s, wrote him a letter after reading the story: “This is it, this is pure Gonzo,” Cardoso wrote. “If this is a start, keep rolling.”

That letter, the first use of the word “gonzo” in connection with his work, was the beginning and the end of Hunter S. Thompson. “I thought, ‘Holy shit, if I can write like this and get away with it, why should I keep trying to write like The New York Times?’” he would say later. “It was like falling down an elevator shaft and landing in a pool full of mermaids.”

Thompson would eventually lose the thread, getting more and more high on his own supply until he was a deranged caricature of himself, a gibbering, yawping clown who let the demons drag him down. (Will Leitch wrote a painful column about meeting Thompson near the end.) He committed suicide in 2005, and aside from a few ESPN columns like this darkly brilliant prophecy of what was to come after 9/114, he hadn’t written anything coherent or incisive in decades.

But “The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved” still stands as one of his signature achievements, and justifiably so. I read it every year around this time, and I recommend you do too. Suspecting everyone in your field of vision is secretly scheming your assassination is a hell of a fine way to get your heart racing on Derby Day.

Bonus: Derby Day drinkin’

Watching the Derby without a drink in your hand is like spending the Fourth of July not blowing up everything in sight. What’s even the point?

Quaffing a Mint Julep at the Kentucky Derby is like having a pimento cheese sandwich at the Masters: customary and expected, even if there are so many better options available. So we’re going to stick with the classics.

The traditional Mint Julep has a few essential elements: fresh mint, crushed ice, bourbon, simple syrup. Mix in pretty much any order and you’re good to go … if you want just a basic Churchill Downs infield drink. Let’s change that up a bit with a creation from the great Scott Hines of Action Cookbook: the Toasted Julep.

This requires some advance preparation, so if you’re reading this on Saturday morning, get cracking. The secret here is in the simple syrup: specifically, in the sugar you use to make the simple syrup.

First, you’ve got to toast the sugar. (Note: do not use an actual toaster for this purpose.) Fill a 9x13 glass dish with a 4-lb. bag of sugar, then cook it in the oven at 300 degrees for two to four hours. While cooking — this is important — stir it every half-hour or so to prevent burning, which will really kill the taste of your future julep.

(Scott wrote a comprehensive, fascinating story on what the Louisville of today is like during Derby Week. Give that a read while you’re waiting for your sugar to toast.)

The sugar will take on a sandy hue and begin to smell of caramel. When you’re happy with your creation, take it out of the oven, allow it to cool — which will take awhile — and then use anywhere you’d use sugar for a richer, toasty experience.

Now you’re ready to make your simple syrup. Most syrups are a 1:1 ratio of sugar poured into water on medium-high heat. I’ll often throw in ginger, mint or citrus to add a little complexity, but not for this recipe — the toasted sugar alone will carry the day. Mix this in a 2 cups-to-1 sugar-to-water ratio until the sugar dissolves, and boom: amber crack, perfect for your julep.

Next, assemble your crew:

2 ounces bourbon (Four Roses for friends, Bulleit for friends of friends, Woodford Reserve or better for yourself)

1/2 ounce of toasted simple syrup (this stuff is sweet as hell, any more than that and you’re making Kentucky Kool-Aid)

Lots of crushed ice

Mint sprigs

Muddle the mint in a metal julep cup or Derby glass5, making sure to run a sprig around the rim. Fill to the top with crushed ice, pour the bourbon and syrup over the top, and begin talking about horseflesh and post positions like a Kentucky colonel. (Lead with this bit of trivia: no horse has ever won the Kentucky Derby from the 17th post.) Enjoy, and I’ll see you on the rail. If you could spot me a twenty, I’ve got a good feeling about No. 3 in the fifth …

This has been issue #54 of Flashlight & A Biscuit. Check out all the past issues right here. Feel free to email me with your thoughts, tips and advice. If you’re new around here, check out some of our recent hits:

A journey to the heart of the real America: Buc-ees.

What it was like to cover the Beijing Olympics inside a locked-down China

How Richard Petty learned that Daddy won’t always let you win

The joy of a really terrible Southern accent

If you dig this newsletter, share it with your friends. Invite others to the party, everyone’s welcome.

To be fair, a whole lot of things do suck right now. But not everything.

Non-white, non-male journalists tend to have better role models, or at least less cliché ones.

The Onion brilliantly skewered the legions of HST-wannabes in this 2005 article. Even if nobody ever really wrote a story headlined “Fear, Loathing At The Owensboro Parks And Recreation Department,” thousands of gonzo babies wanted to, and that’s enough.

“Make no mistake about it: We are At War now – with somebody – and we will stay At War with that mysterious Enemy for the rest of our lives.”

The last time I was at the Derby, they served juleps in actual glasses in the infield. I cannot stress enough what a terrible idea this was. Two or three of those and you’re stuck carrying glasses around … which means you quickly alight on the idea of throwing the glasses into the air, often over the top of a food truck or souvenir hut. The glass, being glass, does not bounce when it hits the ground on the other side.