Freddie, Chipper, Murph and the saga of the Braves' 'golden boys'

On how Atlanta embraces its stars ... and who should be next

Welcome to Flashlight & A Biscuit, my Southern culture offshoot of my work at Yahoo Sports. Thanks for reading, and if you’re new around here, why not subscribe? It’s free and all.

Baseball’s back, and today at F&AB, we’re out at the ballpark. You can buy your own peanuts and Cracker Jack, though. That stuff’s expensive as hell these days.

On Monday, the Atlanta Braves (and, by association, their fans) will have to endure the baseball equivalent of going to an ex’s wedding. Atlanta will travel to Los Angeles, where the Braves’ golden boy of a decade, Freddie Freeman, is now part of the team that’s baseball’s answer to Alabama football. It’s always strange, seeing a familiar player in a new uniform, but for Freeman — who’s part of the most exclusive club in Atlanta sports — it’s downright unsettling.

Braves fans have always had a strange, provincial, possessive relationship with their players. This isn’t unique to Atlanta; every fan base has players it claims as its own, players who through some combination of loyalty, longevity and performance seem connected forever not just to a franchise, but to a city itself.

It’s all sentimental hogwash, fostered by the teams (and, uh, the media) far more than the actual players themselves. Loyalty’s a nice perk as long as the tall dollars are rolling in, but if the money’s right, the player’s gone, with little more than a PR flack-written Instagram post and thousands of suddenly-outdated jerseys to mark their passing.

Freeman parted ways with the Atlanta Braves shortly after the lockout ended, bringing an end to an Atlanta career that culminated in catching the final out of a world championship. While there are plenty of very good baseball reasons for Braves fans to both bemoan Freeman’s departure and feel OK about his replacement, I’ll leave that actual sports analysis for the day job. (Short version: Braves fans upset that Freeman would leave his forever home to move to a new city in search of greater wealth might want to remember that the entire team did the exact same thing a couple years back.)

Here, I want to get local and dig into why it is that certain players connect with Atlanta fans in a way that goes far beyond just cheering when their at-bat music plays.1

Much of Atlanta’s borderline-clingy relationship with certain stars derives from the team’s ancestral DNA. Atlanta spent so many years as a backwater franchise — a mild speed bump for the Dodgers and Reds, unknown to the Yankees and A’s — that fans of the ‘70s and ‘80s gravitated to local Atlanta talent like Dale Murphy and Bob Horner. It was always a thrill seeing Murphy in the All-Star Game lineup alongside Joe Morgan, Johnny Bench and Steve Garvey, even if it felt a little like rooting for Christian Laettner on the Dream Team or Hawkeye in the Avengers.

Murphy was the first of Atlanta’s “golden boys,” the players most deeply connected to the city on some elemental level. They were the players on the front of the programs, on the tickets (back when paper tickets were a thing) and the billboards, their names on the backs of thousands of t-shirts across the South.

Somewhere along the line, the Braves got good. Not in time to bring Murphy along with them, alas; he was shipped out in 1990, just before the Braves went on a decade-plus run of playoff appearances2, to make room for the next link in the chain, David Justice. It was Justice, in fact, who coined the term “golden boy,” referring to then-brand-new rookie Chipper Jones.

The last days of Chipper’s career overlapped neatly with the first days of Freddie’s, and the two were forever linked when Jones had to rescue Freeman during a snowstorm. It was an event so strange the Braves even turned it into a bobblehead:

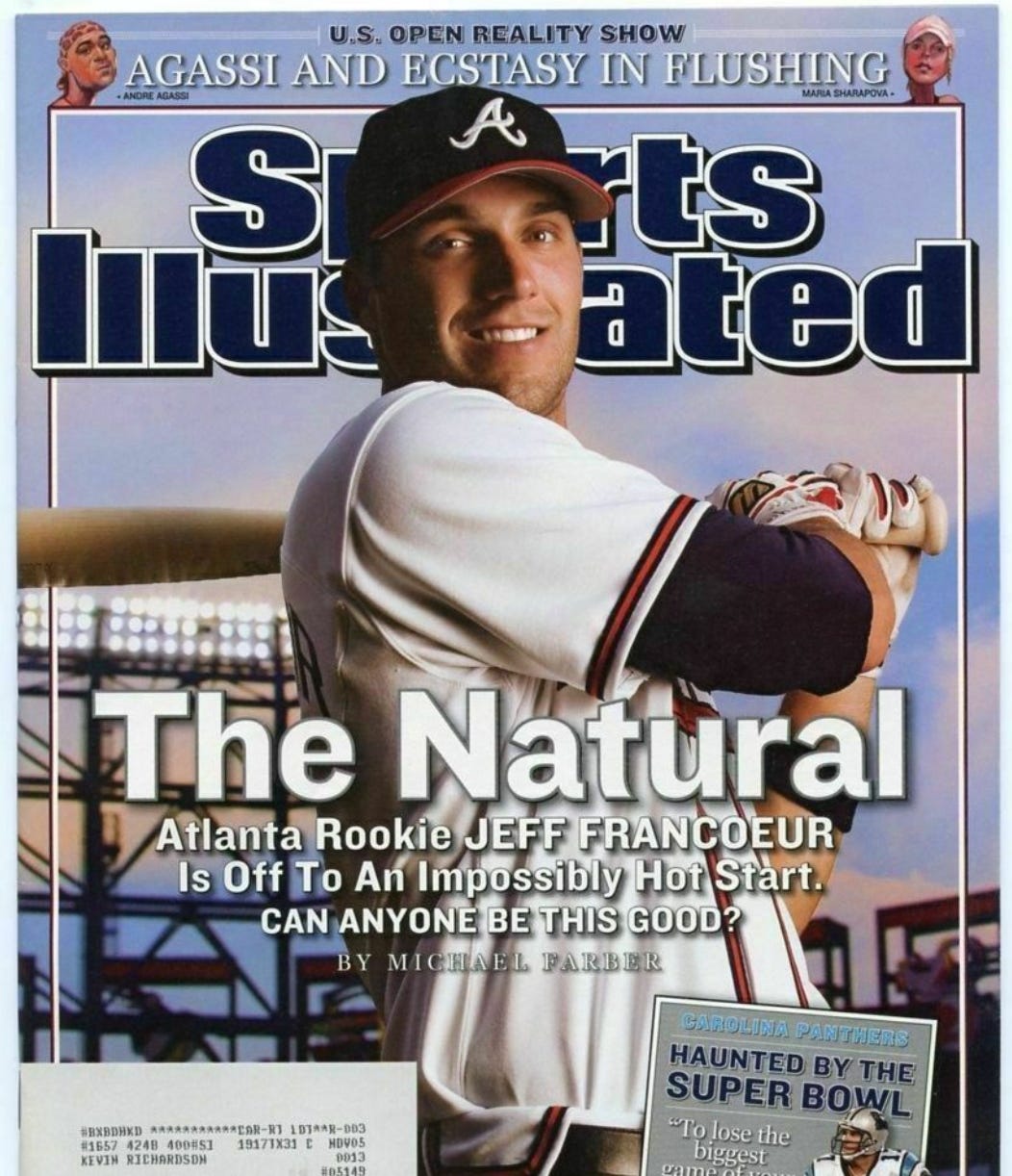

There have been a few near-golden boys, like Jeff Francoeur, who was so good so fast that he ended up on the cover of Sports Illustrated back when that was still a marker of cultural supremacy:

“Can anyone be this good?” Well, yes, but his name isn’t Jeff Francoeur, it’s Shohei Otani, and he was 12 years old when this picture was taken. Frenchy peaked quickly and is now a Braves announcer, but he remains, without exception, the friendliest Brave ever to wear the uniform.

Among the Braves’ longtime stars, you can draw a direct line from Murphy to Freeman, nearly a half-century of reliable baseball craftsmanship. They all have certain attributes in common, starting with the fact that they’re all home-grown — the Braves drafted them out of high school, nurtured them through the minors, and brought them up to The Show — where, almost without exception, they were preternaturally successful right out of the gate.

Worth noting: there’s a deep streak of do-your-job, act-like-you-been-there running through the Braves fanbase. Players who put the name on the front of the jersey ahead of the name on the back always seem to click with the Cobb County swath of the fanbase. And if this sounds like code, well, you’re not wrong. I’m not going to say all Braves fans are racist — I’ll save that idiocy for the Brooklyn bloggers who parachute in with every October — but I will say that there are a whole lot of Braves fans who find it a lot easier to root for Freeman than, say, Ronald Acuña Jr. (Though perhaps not anymore...)

So who’s the next link in the chain? Based on the above criteria, the leading candidate is shortstop Dansby Swanson. You don’t get more local — he grew up playing baseball 10 minutes from Truist Field. Swanson also fielded that final out of the 2021 World Series, throwing to Freeman. He’ll need to pick up his production — legends don’t bat ninth — but he’s got everything else already lined up. Matt Olson, who joined the Braves in the Freeman trade, could be grandfathered in because he played high school baseball in Atlanta before his professional days in Oakland.

But if you want my pick, I’d say Atlanta needs to fully embrace the exuberant joy that is Ronald Acuña Jr. Yes, he’s still learning English, and yes, he’s exactly the kind of player — loud, boisterous, look-at-me — that infuriates a whole swath of old-school Braves fans. On the other hand, he’s ridiculously talented, he makes every play in the outfield an adventure, in a good way:

When he’s healthy (i.e. not right now), he’s the kind of guy you plan your beer runs around so you don’t miss any of his at-bats:

Acuña shouldn’t get the label “golden boy” for a whole raft of pretty obvious reasons, though it’s not that much worse than a nickname he picked up in the minors: “El Abusador,” or “the abuser,” a reference to the way he hit baseballs. The “golden boy” moniker, like a whole lot of old-school iconography, belongs in the archives. But the idea it represents — the best Atlanta has to offer, carrying the hopes and dreams of the city on his shoulders without even straining — should live on.

If Acuña leads the Braves to another World Series championship in less than another 26 years, he’ll deserve all the love he gets.

This has been issue #52 of Flashlight & A Biscuit. Check out all the past issues right here. Feel free to email me with your thoughts, tips and advice. If you’re new, check out some of our recent hits:

What it was like to cover the Beijing Olympics inside a locked-down China

How Richard Petty learned that Daddy won’t always let you win

The joy of a really terrible Southern accent

If you dig this newsletter, share it with your friends. Invite others to the party, everyone’s welcome.

If you’re a longtime Braves fan, you’ll never again hear the opening notes of Ozzy’s “Crazy Train” without unconsciously saying, “Now batting … Number 10 … Chipper JONES!”

During that era, which ran from 1991 to 2006, they won the World Series an incredible — hmm, Wikipedia doesn’t seem to have a record of that. Must have been five or six times with that pitching staff, right?