Hellfire & White Lightning, Part III: Sugar and blood

The conclusion of a three-part tale of moonshine and murder.

Welcome to Flashlight & A Biscuit, my Southern culture/sports/music/food offshoot of my work at Yahoo Sports. Thanks for reading, and if you’re new around here, why not subscribe? It’s free and all.

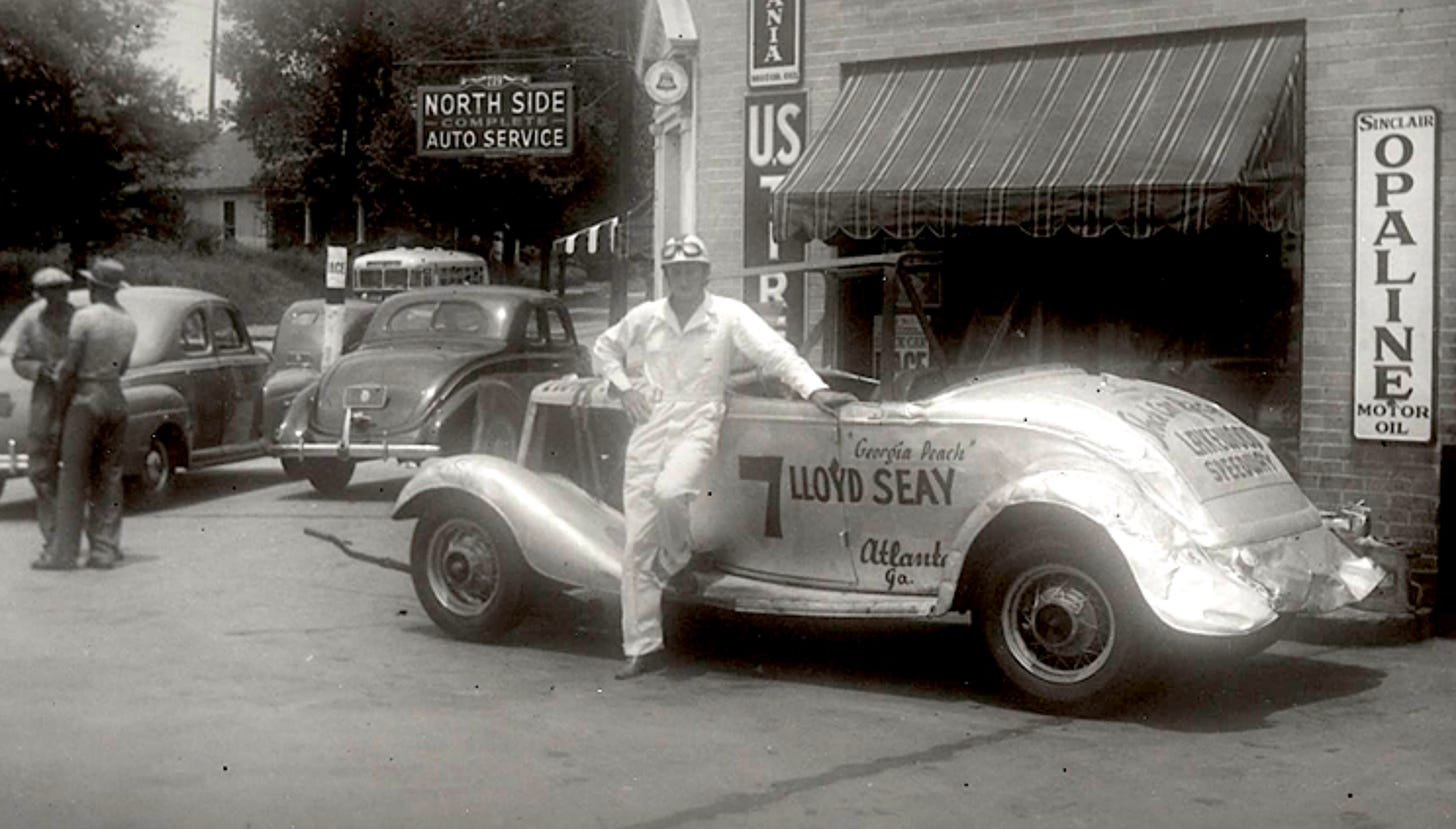

Time for the concluding chapter in my three-part story about one of history’s greatest drivers, a 1930s-era moonshiner-turned-racer named Lloyd Seay. Catch up with the previous installments here:

When last we saw Lloyd, he was trying so hard to outrun his life of moonshining. But that life doesn’t let you go so easily…

Moonshine requires vast quantities of sugar, quantities measured not in cups but in tons. The presence of sugar alone was enough to get local law enforcement interested in goings-on. Sugar itself was currency, a commodity that was prized and necessary. You didn’t mess with a man’s moonshine, and you didn’t get between him and his sugar.

Labor Day weekend, 1941. Lloyd Seay had just won the biggest race of his life, and he barely hung around long enough to enjoy it. As fireworks burst over Lakewood Speedway near Atlanta, as Seay was reveling in the joy of his accomplishment, local sportswriters were already building the foundations of his legend. “A lead footed mountain boy who didn’t care whether he was outrunning revenuers or race drivers just so long as he was riding fast,” one dubbed him.

Seay won $450 — nearly $8,000 in 2020s dollars — for capturing the title at Lakewood, and that kind of immediate cash drew immediate interest. Before the fireworks had even faded from the sky, Seay and his brother Garnett, who went by Jim, headed back to Jim’s house near Dawsonville to sleep off the night’s buzz.

But cash draws flies, and the brothers weren’t home for long before a cousin, an angry squat fireplug of a man by the name of Woodrow Anderson, showed up.

Anderson and the Seays had long been in business together running moonshine. But now that Lloyd had struck it rich, Woodrow wanted a taste. Lloyd had bought several 50-pound sacks of sugar a few days before, but instead of paying for it, he told the grocer to put it on Woodrow’s tab. Whether Woodrow had authorized that or not was irrelevant at this point; he now wanted to be paid $120. Immediately.

Woodrow Anderson and law-abiding behavior had only a passing familiarity. He and an uncle once nearly beat to death a man whose cows had wandered into Woodrow’s yard. He once shot his own dog on a hunting trip. He’d done two stints in prison. He was not a man with whom one messed.

On this night, he banged on the door, waking the Seay brothers up. They agreed to go with Woodrow, and wanted to follow him in Lloyd’s car. No chance, Woodrow said, insisting that the brothers ride in his beat-up Model A.

“How will me and Jim get back home?” Lloyd asked.

“I’ll bring you back,” Woodrow replied.

So they began a dark drive to Dahlonega, a dozen or so miles away, along the same roads where Lloyd had been running moonshine for the last few years. Jim suggested that they head to the home of their mutual aunt, the same one who’d had the book thrown at her three years earlier for cussing out a cop.

“She’s aunt to all three of us,” Jim said, “let her do the figuring.”

Woodrow shot that idea down fast. And then, as he drove up Highway 9, he offered up a chilling question, asking if Lloyd still thought the No. 13, the number of his winning race car a few hours before at Lakewood, was lucky.

“I reckon so,” Lloyd replied. “Why?”

“Don’t be too sure of that,” Woodrow said. He pulled into the driveway of his father’s house and said he needed to put some water in the car’s radiator.

What happened next remains a matter of some significant dispute.

According to Woodrow, Lloyd and Garnett then attacked him. “One word had just led to another,” he later said. “The first thing I knew, we was quarreling, then I was running, then I was shooting. That’s all there was to it.”

He claimed he broke loose from their clutches, ran into his father’s house, and grabbed a pistol from under his father’s pillow. The Seays chased him, in Woodrow’s telling, and as Woodrow held the gun, they refused to back off. He warned them not to come any closer, but they kept advancing, and he had no choice but to fire.

“I run through the house and got my daddy’s .32 Smith and Wesson pistol and tried to get in my car,” he would say later. “They wouldn’t let me get in, and it looked like they were about to give me a whuppin, so I started shootin’.”

He claimed that Lloyd’s final words were a confession: “Woodrow, I done you wrong and I’m sorry.”

Jim Seay recalled it differently. Woodrow got out of the car, walked to the front, popped the hood, and pretended to unscrew the radiator cap. Then he reached into the engine compartment and pulled out something that he tucked in the front pocket of his overalls.

Returning to the side of the car, he told Jim to get out “if you don’t want to get mixed up in anything.” Then he pulled a .32 from his coveralls, waved it around, and screamed, “By God, get out!”

Jim did as he was told, and then Woodrow leaped into the back seat and began beating on Lloyd with both his fists and the pistol.

“Put the gun up!” Jim yelled.

“You black son of a bitch,” Woodrow yelled, “I’ll shoot you first!”

He fired, and the bullet tore through Jim’s neck and right lung. Blood flowed, thick and slick, through his fingers.

Committed, Woodrow turned the gun on Lloyd and, without uttering another word, fired, hitting Lloyd straight in the chest. The bullet ripped through his heart and Lloyd fell backward onto the dirt. Woodrow loomed above him.

“Why?” Lloyd whispered in his final moments. “Why’d you shoot me?”

“Goddamn you,” Woodrow growled, “you know what I shot you for.”

Lloyd lay in the red dirt, begging for water. Woodrow didn’t even acknowledge him. Seay lifted his head, looked at his brother, his last thoughts of his cousin and mechanic, Raymond Parks.

“Tell Raymond…”

And then Lloyd died.

Woodrow dug in Lloyd’s pocket and found the money he’d won at Lakewood, plus a silver dollar Lloyd carried for luck. Woodrow counted out $120 in blood-stained bills and threw the rest back at Jim.

Seay’s death was big news. His story ran on the front page of the next morning’s Atlanta Constitution. Alongside Seay’s tragic story was a report from Europe, where an American-made fortress bomber had been riddled with fire from Nazi planes while on a bombing mission near Brest, France. America was still months away from entering World War II, and the exploits of Lloyd Seay and other moonshiners had been a welcome distraction for many Georgians.

“When not racing,” the Atlanta Constitution dryly noted, “Mr Seay divided his time between Dawsonville and Atlanta.”

The funeral was held on September 6 at the First Baptist Church of Dawsonville. Seay’s body lay at the home of his parents, where truckloads of flowers arrived. Hundreds of mourners later watched his hearse go by, from race fans to whiskey trippers to a few revenuers who respected Lloyd even as they worked to put him behind bars.

To help defray the family’s burial expenses and other costs, drivers including Bill France and Bob and Fonty Flock held a 50-mile benefit race at Lakewood. They raised $831.32 -- nearly $15,000 in 2020s dollars -- for the Seay family, including hiring attorney Pat Harrison of Blairsville to assist Lumpkin County prosecutor Fred Kelly.

Lumpkin law enforcement held Anderson, age 28, without bond. The local sheriff also arrested Anderson’s father, Grover, age 53, who’d been on the property but apparently feeding the family’s animals when the late-night shooting occurred.

A grand jury empaneled to deliver so-called “true bills” — indictments — returned charges of murder, assault with intent to murder, and carrying a pistol.

The trial of Woodrow Anderson began several weeks later, at 9 a.m. on the morning of October 24. Anderson, defended by attorney Fred L. Brewer of Gainesville, pleaded justifiable homicide before Lumpkin County Judge T.S. Candler.

The one-day trial went to the jury late in the evening of the 24th, but the jury failed to reach a verdict. Judge Candler declared a mistrial, and brought in a new jury for a trial six days later.

That jury, after three hours of deliberation, found Anderson guilty, but offered up “a recommendation of mercy,” which took the death penalty off the table. Anderson was sentenced to life imprisonment, but was paroled in 1948.

Seay is buried in Dawsonville Cemetery, beneath a headstone that included a carving of his car and a tiny photograph of Seay behind plexiglass in the car’s driver’s seat. It’s there to this day. Someone switches out the photos once they become too weathered.

“Lloyd Seay probably could have become one of the biggest names ever in racing,” Seay’s old racing rival Tim Flock said in 1979. “If he’d lived long enough, he could have been as big a name as Richard Petty is today.”

He was the most famous victim of the Georgia moonshine era. He wouldn’t be the last. The allure of moonshine, the seductive draw of wealth, the deep Southern desire to stick it to The Man … it all intertwined and drew all of Georgia into a web that would have tragic consequences a decade later.

Wow, whatever could I mean by that mysterious concluding line? Hell, maybe one day I’ll get around to writing the book that I’m hinting at there …

So, thanks for reading all that! Hope you enjoyed it all.

Here are a few more things I wrote this week as a certain Big Game approaches:

The wild story of a Super Bowl ring scam that involved hundreds of diamonds, hundreds of thousands of dollars, and Tom Brady’s three nonexistent nephews

How the NFL stripped Arizona of a Super Bowl once, and how it could happen again

And if you’re in a power-ranking mood, I ranked the best halftime shows, the worst halftime shows, and the worst national anthems. (Whitney is the best, even if she was lip-sync’ing, end of story.)

Enjoy the snacks, the ads, and maybe even the football, and we’ll see you right back here next Saturday, cool?

—Jay

References:

“Driving With The Devil,” Neal Thompson, 2007

”Return to Thunder Road,” Alex Gabbard, 1992

”Wheels,” Paul Hemphill, 1997

A whole ton of old Atlanta Constitutions on Newspapers.com

This is issue #92 of Flashlight & A Biscuit. Check out all the past issues right here. Feel free to email me with your thoughts, tips and advice. If you’re new around here, jump right to our most-read stories, or check out some of our recent hits:

Did Dolly Parton really write “Jolene” and “I Will Always Love You” on the same day?

Wienerman and the Great West Virginia Hot Dog Heist

What happens when “Loserville” starts winning?

What does “Flashlight & A Biscuit” mean, anyway?

And load up a to-go box before you leave:

If you dig this newsletter, share it with your friends. Invite others to the party, everyone’s welcome.

This is not how my grandmother and Uncle Jim told me the story throughout the years, as they say in the mountains, this is hogwash.